Culture is an “inseparable part and vital component of society,” argues Dr. Eva Polyviou. On a conscious or unconscious level, culture governs our everyday lives and shapes our reality. For this reason, she maintains, a reassessment and reorientation of our education is required. “Society, by definition, takes the human being as its point of reference. When this parameter is downgraded for any reason, it is only to be expected that the qualitative characteristics of society will also deteriorate.”

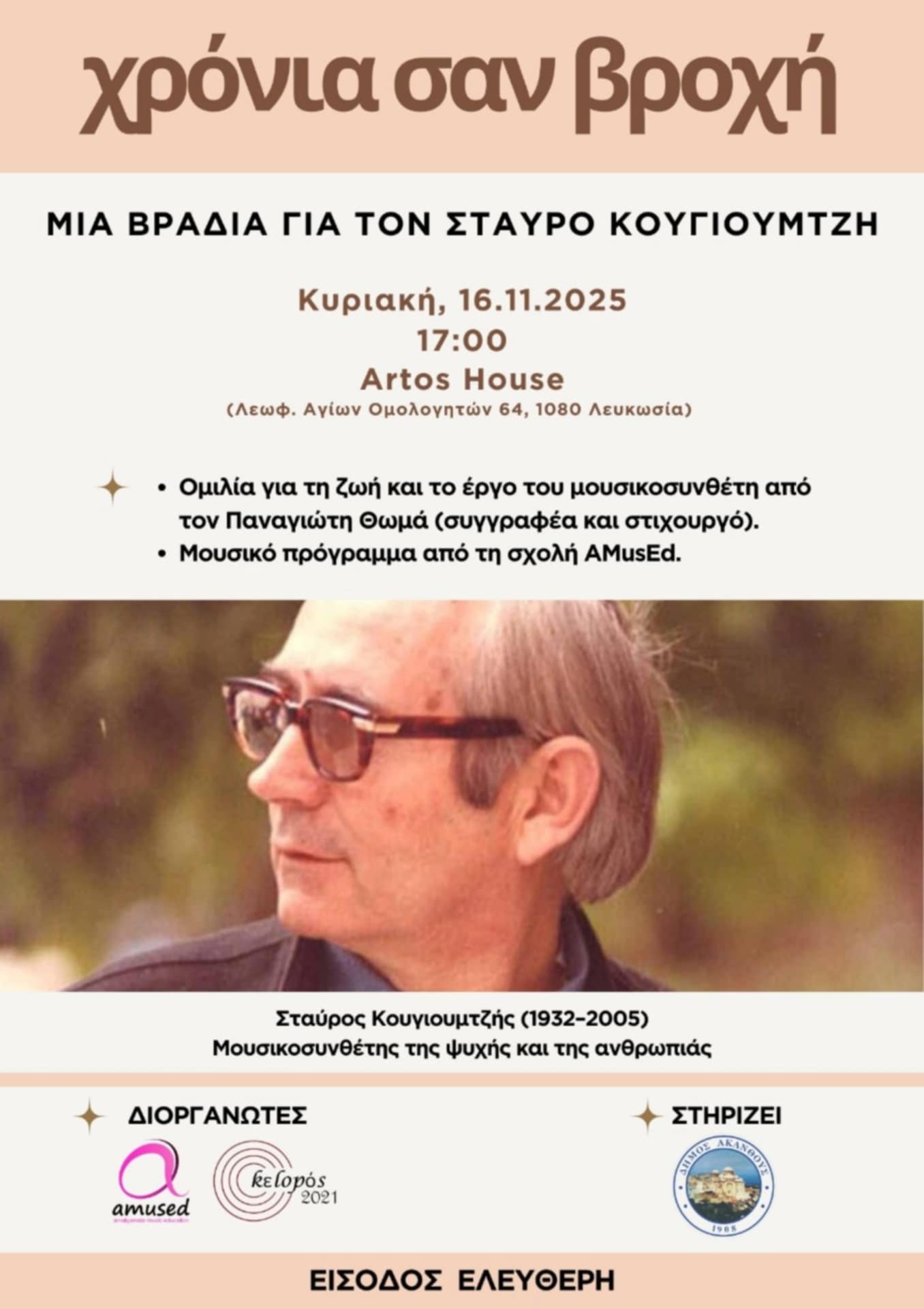

On New Year’s Day 2022, the establishment of the Centre for Literary and Cultural Studies (KELOPOS) was announced. On the occasion of its founding, we spoke with the President of the Centre’s Board of Directors, Dr. Evanthia Polyviou, about this initiative, its aims and vision, as well as about culture more broadly and its significance.

What prompted you to undertake this initiative?

First of all, I would like to point out that behind KELOPOS stands a dynamic group of people who share the same vision, each having followed their own path in the fields of literary research, education, and the arts. It is true that in recent years many noteworthy initiatives have emerged in Cyprus, led by remarkable individuals active in the fields of letters and culture. Nevertheless, we believe that there is still a lack of an autonomous and flexible institution that combines high-level academic research with meaningful cultural engagement, while remaining in constant dialogue with society, its needs and demands, and connecting it to the international intellectual pulse. This is the space KELOPOS aspires to fill, and it is from this aspiration that the initiative itself was born.

Where will the activities of KELOPOS be focused?

The establishment of the Center has two main objectives, which also constitute the two pillars around which its activities will develop.

The first, purely research-oriented objective concerns the study of literature—not only Greek literature or only contemporary literature, but literature in its full temporal and geographical scope, within a comparative and interdisciplinary framework, always aligned with international scholarly research and contemporary challenges. Accordingly, the Center’s academic activity will focus primarily on undertaking and implementing research projects, as well as organizing scientific conferences, lectures, and related events.

The second objective focuses on the promotion of culture. Here, we hope to create a cultural hub through regular interventions, events, cultural gatherings, seminars, and a wide range of artistic activities that will showcase literature and culture while simultaneously opening a dynamic channel of communication with society.

Do you see scope for the institutional consolidation of your activities? Is there an intention to coordinate with institutional bodies?

Not only is there scope for coordination, but I can say that this is something we actively seek. As I have already mentioned, KELOPOS is a flexible, outward-looking organization, fully open to collaboration with other bodies—whether institutional or not, both locally and internationally—provided, of course, that there is a convergence of goals and a mutual willingness for creative cooperation.

Turning to literature and culture may seem like a “luxury” in today’s fast-paced society, which focuses largely (at the grassroots level) on survival and (at the state level) on economic indicators. What, then, can the promotion of culture offer at a social level?

Whether we realize it or not, culture is an inseparable and vital component of society. And when we speak of culture, we are not referring solely to theatrical performances, concerts, art exhibitions, or literary evenings, but to something far broader and deeper, something that permeates every aspect of our lives.

Culture is embedded in every decision we make as a society, whether at the grassroots level or as a state mechanism. All the collective and personal choices we make every day in pursuit of survival, our goals, desires, priorities, the way we perceive our relationship with society and the state, as well as the way the state understands its role and responsibility toward the society it represents—all of these are inextricably linked to culture and reveal its character. Even the degree to which the state—indeed, the government, to be precise—supports or fails to support the cultural life of the country is directly related to our culture.

Therefore, while the promotion of culture may appear to be a “luxury” in a society focused on economic indicators, it is in fact a necessary condition for that society to preserve the values and qualities that will enable it to regenerate, survive, and prosper in a demanding and ever-changing contemporary environment, and ultimately to move forward securely into the future.

To what extent do you think our cultural inadequacy has altered society? Or, to put it differently: has the shift in education toward a more “positive” (STEM-oriented) direction changed the character and qualitative traits of our society?

I will begin with the second question: the positive—or rather STEM-oriented—reorientation of education, aimed primarily at strengthening professions that respond to labor market demands, and the resulting marginalization of the humanities, which we have witnessed extensively in our schools and universities over recent decades. This is a phenomenon particularly pronounced in our country, where small scale and largely traditional social structures make changes more visible, but in reality, it is a problem affecting the entire Western world, with serious consequences for people’s way of life and for society as a whole.

Society, by definition, takes the human being as its point of reference. When this parameter is diminished, it is only natural that the qualitative characteristics of society will also decline. This is, I believe, why in recent years leading universities abroad have expected applicants in the sciences—not only to demonstrate excellence in their chosen fields, but also to present strong performance in subjects such as literature, history, and languages. Some institutions even introduce flexible curricula that allow students to combine the sciences with the humanities—for example, Physics and Philosophy, Mathematics and Literature, Computer Science and Theatre.

In our country, unfortunately, a technocratic mentality continues to dominate education—and not only education—prioritizing specialization in so-called “productive” fields at the expense of intellectual cultivation. The notion that productivity and intellectual cultivation cannot—or need not—coexist is itself a product of our cultural inadequacy and of the erosion it has caused in our society, while at the same time perpetuating and reinforcing that inadequacy.

I am reminded here of a remark by Tzvetan Todorov in his book Literature in Danger: do we fail to see that a future doctor, in order to practice medicine, would learn far more from studying great writers such as Sophocles, Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, and Proust than from the mathematics exams that currently determine his or her fate? Is there a better way to understand human behavior—and therefore better preparation for professions based on human relationships, such as law, economics, or psychotherapy—than through literature?

Do you believe that, in our time, it is possible to produce culture rooted in the distinctive characteristics of a society? Does this make sense in an era of globalization?

We do indeed live in an era of globalization, as you rightly point out—an era in which technology dissolves boundaries in knowledge, culture, and communication, leading to the creation of a global society. Personally, I consider this a blessing and a privilege. At the same time, however, globalization also has its darker side: the production and promotion of mass—and sometimes guided—culture, with all the dangers this entails.

The distinctive characteristics of a society—its values, traditions, and temperament—are the tools with which it can resist this cultural imperialism of our time and preserve its authenticity and autonomy. Only in this way can a society contribute positively to the global cultural and social landscape, while continuing itself to be enriched in a meaningful and creative manner.